“Your house is on fire!!!” You receive a frantic call from your neighbor. “What?!!” you say in disbelief. “Your house. . . it’s on FIRE!”

You are on vacation with your family, halfway across the country. Your home of 15 years is going up in smoke and there is nothing you can do. The sound of sirens drowns out your neighbor’s voice, and you hang up the phone. At first, you say to yourself it’s just a home and we have insurance, but then you start thinking about the marks on the wall chronicling every child’s growth spurts, the boxes of photos of family trips, the painting you made with your daughter when she was 3, the memories of movie night on the back porch. . . Our homes are sacred places. They are repositories of memories.

For Vero Rose Smith, home takes on a broader sense — our planet. She grew up outside a small town in Illinois; her artistically-inclined parents were stewards of a native woodland area that was her backyard growing up.

For Vero Rose Smith, home takes on a broader sense — our planet. She grew up outside a small town in Illinois; her artistically-inclined parents were stewards of a native woodland area that was her backyard growing up.

“So a lot of my early childhood memories are learning plants with my mom, finding where things wanted to grow naturally, seeing how we could help make sure that happened continuously, and being really attentive to the types of life forms that we shared that place with.”

As a self proclaimed “nerdy kid,” she was drawn to the study of the environment and the arts, particularly music, like her father. Growing up surrounded by a native woodland, she saw the effects of climate change first-hand and dedicated herself to educating others about the dangers of climate change. Her initial intention was to return to her hometown, teach biology, and support the arts in her local schools. Her parents’ appreciation and respect for the environment no doubt influenced her interests, but their exploratory view of college freed Vero to seek her own path.

“We are experiencing an extinction in a literal sense – extinctions of other species that we have been cohabitating with on this planet, but we are also at a point of an extinction of human experience. The way that we relate to the planet around us is fundamentally shifting and has been for centuries.”

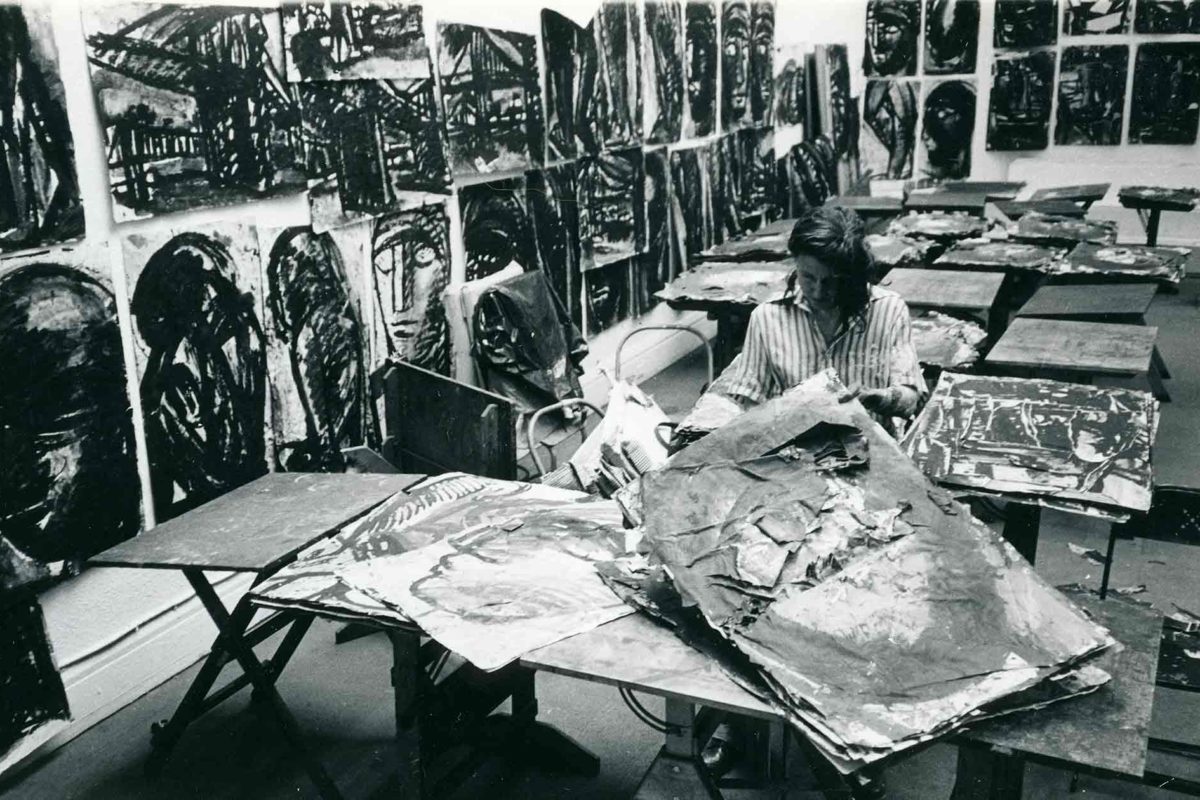

She attended Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois, and majored in environmental science. While teaching was still her primary objective, her studies shifted from basic biology to a more intense scientific understanding of humans’ effects on the environment. Her artistic pursuits also flourished in college, and she triple majored with additional degrees in Art History and Studio Arts. The teaching methods of her painting instructor, Peter Show, helped shape her approach to art and education.

“Art never felt like an interest; it was just an innate way of being.”

Nearing graduation, she found that environmental jobs were scarce given the political climate of the time, and so she opted for a graduate degree in Art History at the University of Iowa, studying architectural history. Her graduate research focused on the evolution and pervasive nature of big box stores in America. Stimulated by the architectural basis of her studies but missing the act of art creation, she went in search of a program that would allow an artistic output to her research endeavors. Therefore, she ventured to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, for a Masters of Design Studies. Here she engaged with a number of faculty, including Krzysztof Wodiczko and Silvia Benedito, whose analytical approach to art and design was highly influential. They also reinforced the importance of art as a visceral and conditional experience.

Nearing graduation, she found that environmental jobs were scarce given the political climate of the time, and so she opted for a graduate degree in Art History at the University of Iowa, studying architectural history. Her graduate research focused on the evolution and pervasive nature of big box stores in America. Stimulated by the architectural basis of her studies but missing the act of art creation, she went in search of a program that would allow an artistic output to her research endeavors. Therefore, she ventured to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, for a Masters of Design Studies. Here she engaged with a number of faculty, including Krzysztof Wodiczko and Silvia Benedito, whose analytical approach to art and design was highly influential. They also reinforced the importance of art as a visceral and conditional experience.

“It’s about creating collective experiences and recognizing our way of being in the world is directly related to how we are with other people, how they are with us, and how that has to be an intentional process for us to continue as a species.”

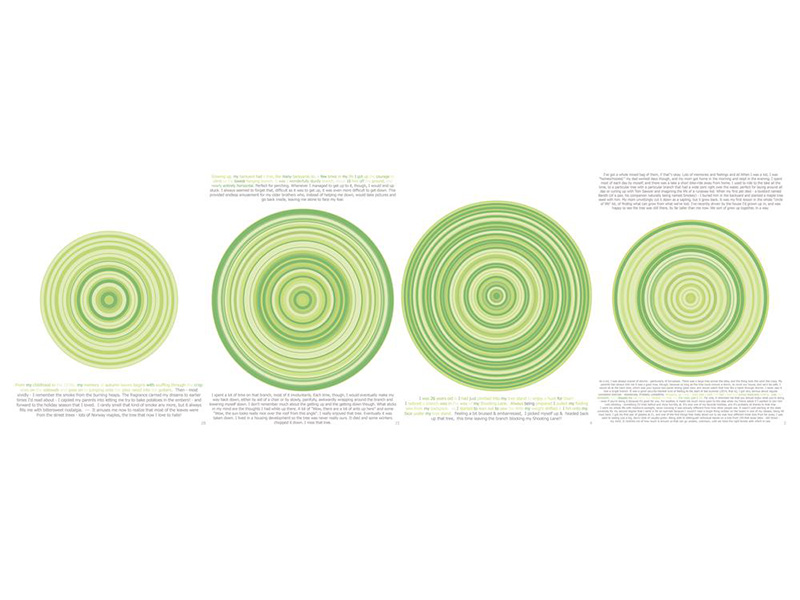

One particularly interesting project to come out of her Masters of Design Studies was SymphonTree. While working at the Harvard Arboretum, she collected people’s experiences with trees in the form of written stories.

“What is in the vast majority of people’s everyday environments? Turns out that it’s trees. So trees appear in almost every single human environment on the planet – not all, but most. In places where tree species are rare, they are even more important. I decided I would start collecting stories of trees, memories of trees, because trees are susceptible, as all things living on this planet are, to the ravages of climate change.”

These stories were then adapted into a new form of musical notation of her own design that allowed for a visual representation of the musical notation in the form of tree rings. Various movements could be layered to form an audible arrangement. (You just have to check it out here).

“Feeling is what activates people to action.”

Following her graduate studies, she returned to Iowa City as a curator at the University of Iowa and as an educator at the University of Iowa and Kirkwood Community College. Her curatorial practice brings together the love of art and art history, the creation of emotive spatial experiences, and the generation of dialogue regarding threats to our environment through her provocative writing. The flooding of the University of Iowa Museum of Art in 2008 has widened the exposure of the University’s collections through shows in various local museums and spaces throughout Iowa, a process Vero has been instrumental in.

“I think it’s really important that people from rural places see themselves in art and are able to access high level gallery-type experiences. . . How are we maximizing our welcome and the fact that this is a public collection has been really important to me. The fact that the people of Iowa are both the funders and the audience for what we collect is so important. So everyone has a small piece of Jackson Pollock’s mural. That’s really beautiful to me.”

True to her goals, Vero is teaching, albeit not a high school biology course. She has taught classes through the University of Iowa and Kirkwood Community College, including Art History, Painting, Public Art, and even a post-apocalyptic class, Art at the End of the World. She goes out of her way to make her classes as culturally inclusive as possible to allow her students to explore art that aligns with their interests.

True to her goals, Vero is teaching, albeit not a high school biology course. She has taught classes through the University of Iowa and Kirkwood Community College, including Art History, Painting, Public Art, and even a post-apocalyptic class, Art at the End of the World. She goes out of her way to make her classes as culturally inclusive as possible to allow her students to explore art that aligns with their interests.

“I want to have a specific invitation for every student who comes into my classroom to show them you are welcome here. You are invited to be part of the world of art, which is really just the world around you, and you’re probably already participating and you don’t even know it. “

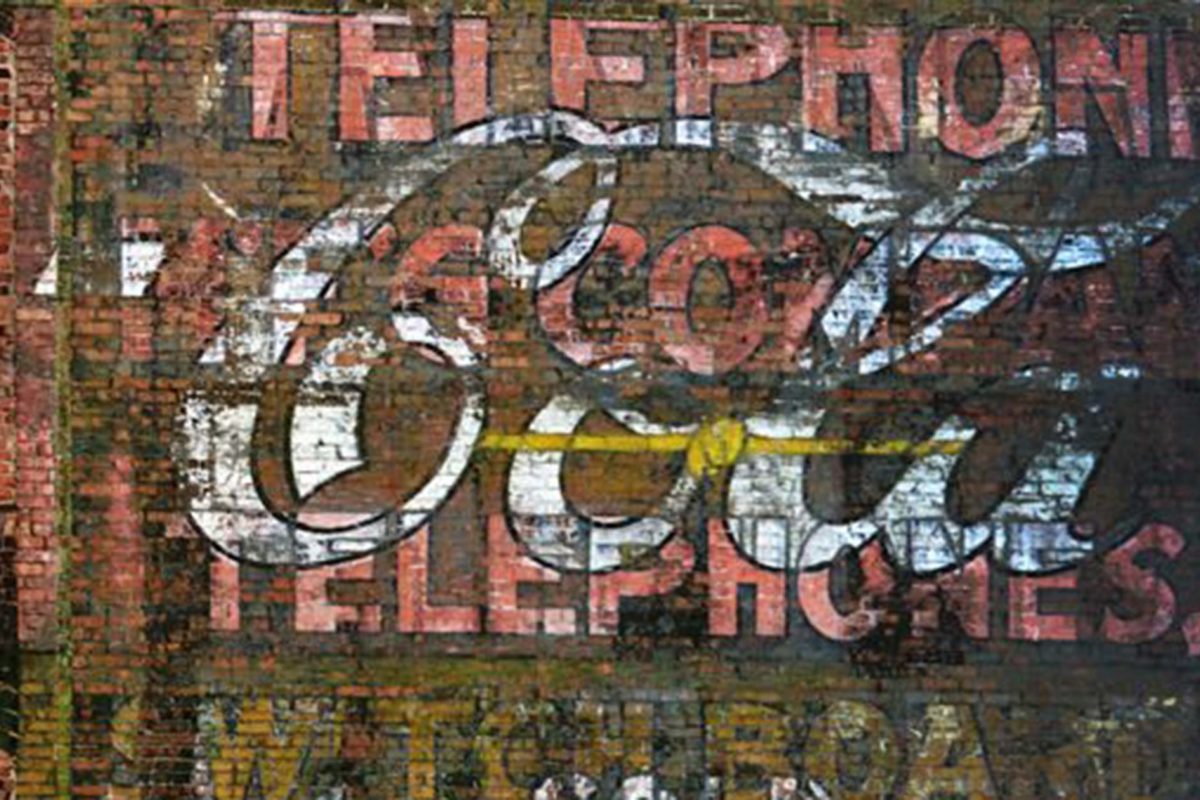

In addition, her curatorial work offers another chance to educate the viewer on threats to our environment, social inequities, culture and gender awareness, and art appreciation through her compelling prose.

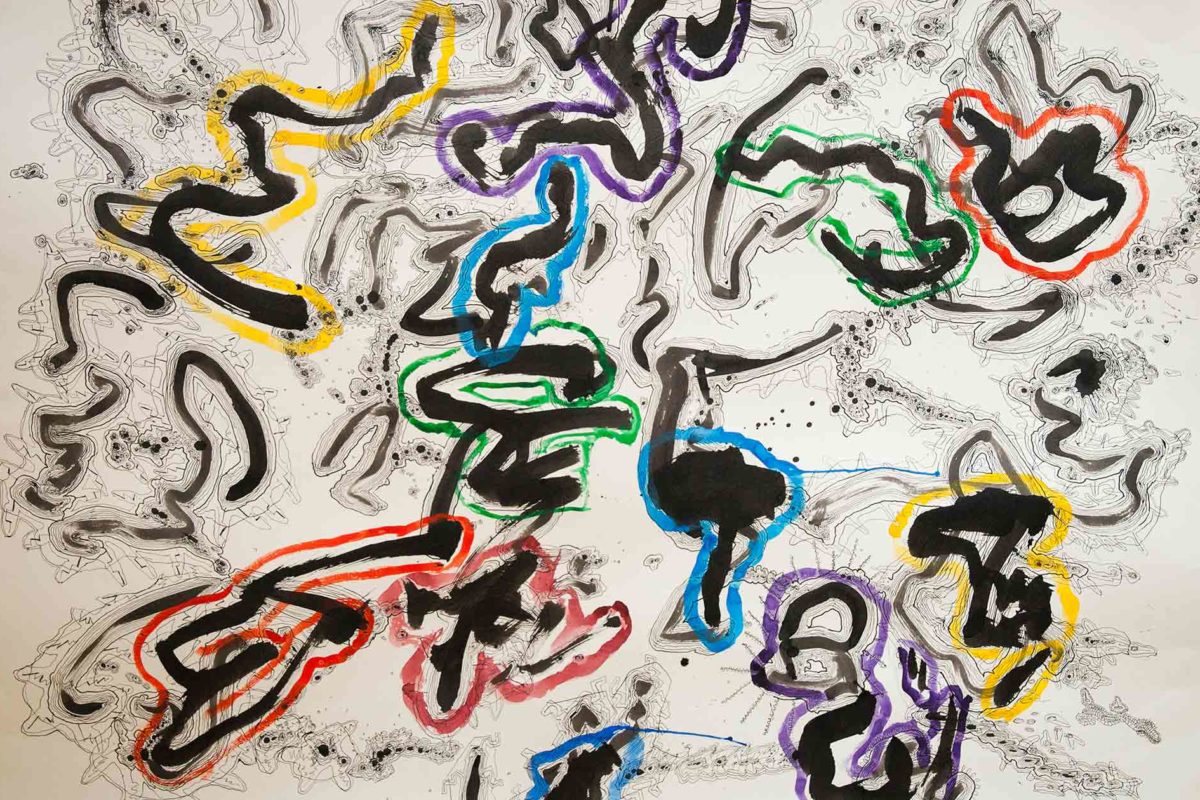

“It was always about this communication of the urgency of climate change, and that is still central to my practice now. So almost every body of work I’ve produced in the past five years in some way has to do with making tangible, large scale data sets about climate change.”

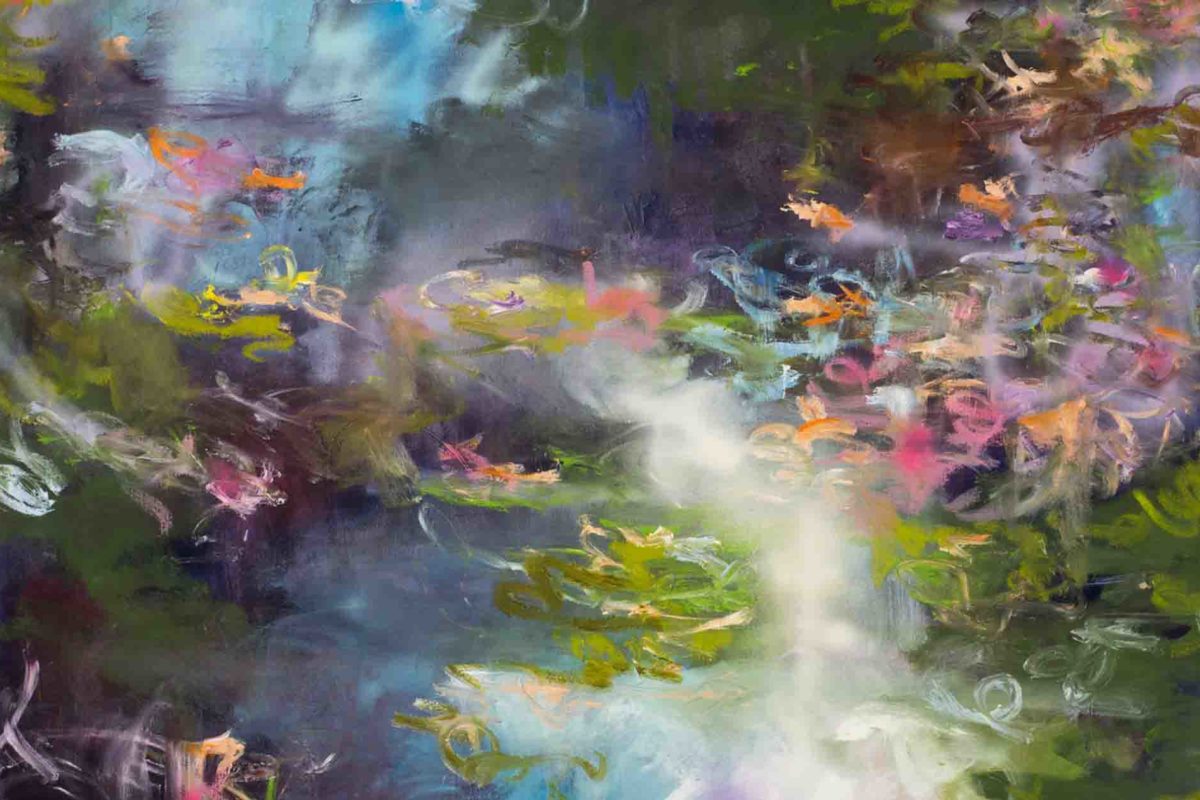

Finally, viewing and participating in her art is an education in itself. Her works are experiential. You have to take your time, absorb the imagery and process what is being said. There is a sober message – one rooted in actual data – regarding our trees, air, water, and environment. Her work reminds you to cherish what you take for granted, for, after all . . .

Finally, viewing and participating in her art is an education in itself. Her works are experiential. You have to take your time, absorb the imagery and process what is being said. There is a sober message – one rooted in actual data – regarding our trees, air, water, and environment. Her work reminds you to cherish what you take for granted, for, after all . . .

Your house is on fire!